When I was nine years old my family moved from Woodhouse Eaves

in Leicestershire up to my grandmother's house, The Croft, at Lakeside, at the

southern end of Lake Windermere. My father had been brought up there.

He loved this place, and I came to love it too. His ashes are scattered

in the clump of trees on the right. The buildings in front of it did not

exist then.

The house was built for a pair of my father's great-aunts.

The extension

on the left replaces what used to be a glass potting shed.

For the retirement of two old ladies it was a generous estate.

Around the house and its gardens were about seventeen acres of

woodland, bought so that nobody could encroach upon the house.

It had three entrances, all on the road from Lakeside to Stott Park

that runs up the west side of the lake. By the main entrance

were stables for a coach and horses, replaced by a subsequent owner

with a double garage, a greenhouse for tomatoes, and

a way into an orchard, which we used as a hen-run. A drive, between

rhododendron bushes and azaleas, led up to the house.

Higher than the house was a rockery, where bilberries, wild

strawberries and heather grew. In front of the house was a massive

tree in a small lawn. Its roots probably went under the house, and

a subsequent owner chopped it down. The second entrance, for tradesmen, ran

straight up from the road to the back door of the house. Between the

main drive and the tradesmen's drive was a kitchen garden, now

landscaped and grassed over. In it was a

raspberry (both red and white) cage, and strawberries, blackcurrants, redcurrants, sorrel, onions, potatoes, carrots, cabbages and herbs of many

varieties. The third entrance, at the back of the house, led through a then uncultivated area of pine trees and daffodils. On the

other side of the road the estate had a bungalow, called the

Tin Tabernacle by my grandmother. This looked out onto a field

running down to the lake. In the middle of the field was a small hut

containing her straw archery targets.

Surrounding house and gardens was woodland, bordered to the south by

the Snake Path, as we called it,

which wound through the woods from Lakeside to the fields

behind the village of Finsthwaite. The picture was evidently taken from what used to be our woodland. The church, St Peter's, has in its cemetery the

grave of Anna Maria Sobieska, wife of Bonnie Prince Charlie, who spent

her remaining days of exile at Jolliver (i.e. July Flower) Tree farm,

out of sight to the left of the picture.

When my friend Jamal Nasrul Islam came to stay at the Croft he played

Tagore tunes on the organ in the church.

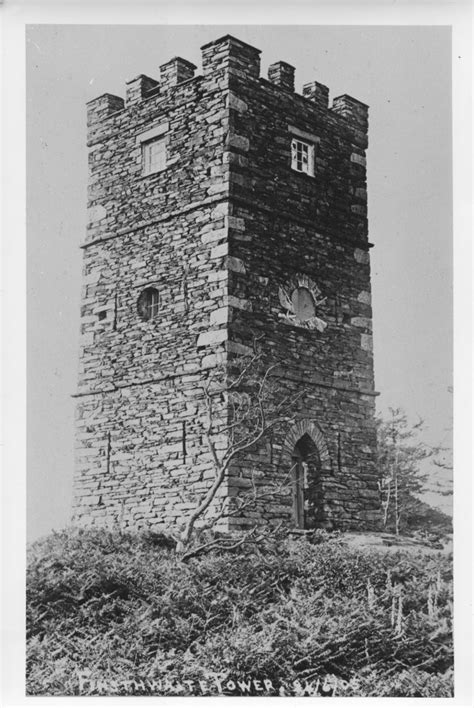

Across the Snake Path and through the woods one may come, at the highest point, to a derelict stone tower erected in 1652 to celebrate Blake's victories

over the Dutch. It overlooks Newby Bridge. It had an evil reputation as some

people were killed by lightning there once.

My grandmother "downsized" to the northern half of the Tin Tabernacle,

and her companion and maid (and my father's nursemaid) Ruth Danson to the southern. She was a remarkable character, with a special affinity for

animals, cats in particular. Ruth had once been engaged to be married,

but her fiance had been ordered to drown some kittens, an act which

Ruth could not forgive. Ruth's voice had an extraordinary quality

which I cannot describe and have never heard in another. She did not

look on humankind with favour, our own family excepted.

There followed blissful years for me and my brother Joe. Less blissful

for my father than he had planned, because his job was still in

Leicester, so he had a long and tiring commute by car. He would stay in Leicester during the week and in the Croft at weekends. My mother loved the Croft, and got on well with her mother-in-law, and also with Mrs Ivy

Jenkinson, a lady from Finsthwaite who came to help clean the house.

Ivy was a brilliant cook, and she would sometimes bring an apple pastie

she had just made. Mr Jenkinson was regarded as a scholar in the

village; people would bring their letters to him to read. Her cousin,

Mrs McDougal, was postmistress at Stott Park, just round the corner

from the Croft.

My father bought us an old-fashioned sailing dinghy, which we kept in

a boathouse which could only be accessed via a path through a

neighbour's property. In the attic of the Croft we found an ingenious

boat-hook, whose handle had a broad cobra-like flange at its

business-end, so that if you dropped it in the water it would lie

flat on the surface, easy to retrieve, instead of the heavy hook

sinking. I never saw its like elsewhere. On the other side of the lake,

at the foot of Gummer's How, lived Lady Gowan. Gummer's How was

just over a thousand feet high, and so qualified as a mountain.

Our house is concealed by trees in the centre of view from the

top.

We had a marvellous view of its evening colours from the Croft.

When her children and grand-children came to stay, Lady Gowan would

organize a picnic on Gummer's How, to which we were often invited.

Wood was collected, fires lit, sausages cooked. All very Swallows and

Amazons. She was good at organizing, as her husband had been a district

judge in India, and she accompanied him on horseback when he toured

his circuit. At the Lakeside Women's Institute bridge games she would

have a small bell at hand, to call for silence so that she could

retell her Indian adventures. My mother relished this. In fact Lady

Gowan was extremely kind, and good company. She let me practice

driving her little car before I passed the test. To be driven by

her was a white-knuckle experience as she showed a lamentable lack of mechanical sympathy. She had a neighbour on her side of the lake

called Colonel Sneed, with a daughter called Idonea.

My brother and I each had a bicycle. We kept them in the stables.

Once Joe and I bicycled to Ulverston, about twelve miles away.

My mother put me in charge of my younger brother, but this was

a vain expectation because he was an independent soul, and

he soon lost me in the back streets of Ulverston. Eventually,

I just had to return without him, anxious about what my mother

would say. In fact she was out, I forget where. I remember

sitting in the hayloft of the stables trying to keep calm by

regulating my breathing, as I had learned from a book on Hatha Yoga.

Of course, Joe returned in his own time, and before my mother

got back, much to my relief.

My mother did not drive ("temperamentally unsuited" according

to her driving tester). Various vans came round once a week - a

baker, a butcher, a grocer - which required careful economy by

my mother. We had help with the garden from Harry Conway, a gentle

giant of a man whose main job was to lead a road-mending gang

for the council. He could do anything - dry stone walling, building,

coppicing, lambing. My father gave him my grandmother's half of the

Tin Tabernacle when she died.

The nearest bus service was at Newby Bridge, about two miles to

the south, on the other side of Lakeside. I had permission

from Mr Wren, who owned the farm at Newby Bridge, to leave my bicycle

in one of his barns whenever I took the bus. Wren's farm lay on the

river Leven. Tragically one of his children was found drowned there.

She had slipped on a stone and concussed herself.

Lakeside had a railway station, a terminus of what had once been

the Furness Railway. The station was also a terminus for the steamers

that ran up the lake to Bowness and to Ambleside. When the railway

was running passengers could get straight off the train onto a

steamer, or perhaps go upstairs to the restaurant and throw tidbits

to the gulls from its balcony. The steamers were the responsibility

of Jones the Boat, who lived in Lakeside and owned a Morgan

three-wheeler.

I remember vividly the smell of vegetation, like that of a rain forest,

on the road from Newby Bridge to Lakeside. The westward side was

thickly wooded. There were more open fields on the eastern side,

and in them some old rusting "flying saucers" - farm machinery

perhaps. I imagined that alien creatures had abandoned their

vehicles and were now hiding in the woods, taking note of any

human activity.

The local "poacher" had a beautiful spaniel called "Lady" and a high

squeaky voice. The standard arrangement was that he would poach game

at will, and leave a portion of his take with the landowner as

payment. Thus we came to have rabbits and pheasants for supper

sometimes. Never deer, however. The part of the wood nearest our

orchard had masses of wild garlic, which stank horribly when it

rotted. We once came across a fawn there, no doubt using the stink

to hide its own scent from predators. We were careful not to approach

it, lest its mother become confused.

We had a very healthy outdoor life, going for long walks, rain or shine,

sailing on the lake, or bicycling. I knew every bush and tree in our

own wood, and often in woods that were other people's property. I was

even accomplished at running through the woods in the dark. I never

sustained a scratch.

Above Finsthwaite was an artificial lake

called High Dam, and it was there that I once had an extraordinary

experience while exploring by myself. There was a tree of great

beauty and I was convinced that it had revealed something of

itself to me. It was as if it were a gracious intelligent being, utterly

uninterested in human matters. It sounds daft, and probably was, but

I was thunderstruck by the experience. I felt grateful, and slightly

scared. I could not tell anybody about it, of course.

I had another transcendent, wonderful experience. It was a fine day,

with a cool breeze and little puffy clouds. I was by myself on my bicycle

on the road out of Low Wood going toward Holker Hall. There was no other

traffic. The grasshoppers in the grass verges were loud. The silver

birches in the marshy ground of the estuary to my right seemed out

of a silk-screen painting, and behind them were mountains in the

distance. I realized that I was blissfully happy. My cup was running

over. I felt a profound gratitude for my existence. I knew that this

experience would always be with me, in some sense that I could not

grasp. Later in my life, at university, I had other similar experiences

which I felt were rooted in this one. I treated all of them gingerly,

with reverence, determined to be both rational and open-minded. What

else can one do?

As a child one hears one's parents talking about their own childhood,

without, in my case, really understanding the relationships. Only

later in my life did I appreciate my father's background.

His mother

had been brought up at Longlands, a beautiful estate outside Cartmel.

Her mother, my father's grandmother, Louisa Augusta, was rather pious,

and taught Sunday school at Cartmel Priory. The south window in the

Priory was a gift of her family, the Barkers. Unfortunately my

great-grandmother was also very puritan, and believed that enjoyment

of any kind was wicked, so perhaps it is not surprising that her

husband, John Barker, took to drink. A family joke is that he would

ring the bell for his servant and then say in lordly tones

Bring me all those things that I require. The Barkers had made their money

from a gunpowder factory in Low Wood, charcoal being a substance

produced in abundance by coppicing the woods in the locality.

My father's father had doubtless been chosen as a suitable son-in-law by the Barkers because his father, George Henry Wraith, had been

three times mayor of Spennymoor and once its member of Parliament, and had founded the Alderman Wraith Grammar School there. Alas, this

respectability had concealed an unreliability with money, and after

siring three children he was persuaded to decamp to South Africa with a pension, on condition he should not return. My father's sister, Maria,

once showed me a drawing made by her mother of my grandfather

expatiating on the virtues of Tiptree's marmalade. He swore it was the

only marmalade he could eat, but unknown to him his wife had decanted

a quite ordinary brand into a Tiptree's jar which she had put aside for that purpose.