| Two Family Dinner Parties |

| Therapeutic Games |

| A Female 'Stalky & Co.' |

| Nicholas |

| Return to previous page |

In 1902 my mother married a 'foreigner' and a much travelled man, which in those days seemed a very romantic thing to do. My father was a true cosmopolitan and his enormous family (he was one of fifteen children) were scattered all over Europe and Asia Minor. The family home was in Constantinople, my grandfather Ukrainian and my grandmother Hungarian. They were Jewish, and family ties and family hospitality were very important to them. Amongst the family they always spoke French, though most of them had seven or eight languages at their tongues' end. My father spoke ten languages fluently and it was only by the care and perfection of his English speech that one realized that he was not using his mother tongue. No doubt in 1902 when he had been living in England for only a short time, he was not so fluent.

My mother's honeymoon must have been something of an ordeal for a young English girl who had never been abroad in her life and who spoke only school-girl French. She was taken around to meet all the relatives, and I think probably the most surprising element of her visits was the warmth of emotion that was freely displayed. She had been brought up 'not to make a fuss', and to the day of her death she never relaxed her British 'stiff upper lip'. This was rather surprising as her own family was not Anglo-Saxon at all and stemmed from Irish and Welsh grandparents. Despite the 'stiff upper lip' our own family life was full of drama - not surprising, perhaps, when one thinks of the mixture of Celt and Slav.

One day when she was staying with my father's eldest sister, she had to face yet another family dinner party arranged so that the bride might meet yet more relations. My mother described the day as starting and continuing in an atmosphere of tragedy, doom and drama! She had no idea what was taking place. The men paced the floor, everyone was shouting and gesticulating, the cook had given notice, and two teen-age daughters rushed from the room in tears. The voices were so loud and rapid, and the gestures were so violent that my mother became really frightened. At last she got my father in a corner. He was shouting with the best of them. 'Josef, what is it? Whatever is the matter?' 'Oh, my dear girl,' was the reply, 'It's nothing, they are discussing how many drops of lemon juice to put in the mayonnaise for tonight.'!

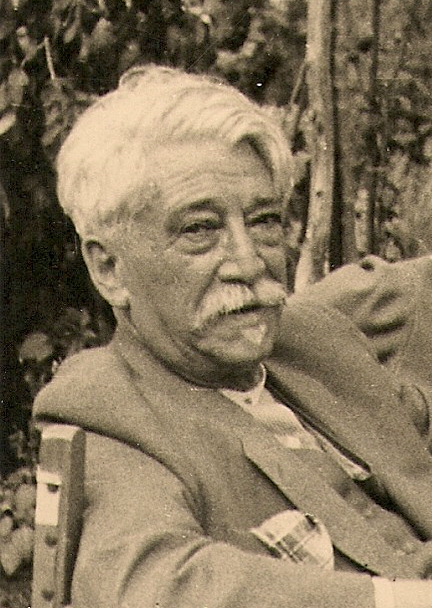

As a small girl I remember family dinner parties, which of course we three children did not attend. We were dressed up, the two little girls in broderie anglaise, and our elder brother in a white sailor suit, and we were escorted to the dining room in time for dessert. There we were allowed fruit, nuts and even a sip of wine. I dimly remember sitting on the knee of some kindly elderly uncle while he peeled a peach for me, popped grapes into my mouth, and asked for one of my red ringlets for his watch chain in payment. I also remember boldly asking for more of something (I forget what) and my mother refusing, saying I had had enough. Uncle Moritz (he had no children) turned on her with blazing eyes and bristling moustachios, exclaiming, 'You are cruel! Take zem all, my tarling tear!' and emptied the whole dish on to my plate. No doubt I rammed as much as I could into my mouth before it was sternly removed, and no doubt I gave my mother a smug triumphant look.

Quite recently when I was visiting my brother, now over seventy years old, we were laughing together over some of the absurdities of our childhood. Suddenly he said, 'Do you remember the drama over "Who Bit the Cucumber?"'. No, I had no idea what he meant. 'I still feel guilty about it', he said, and he recounted the story of a day when some important dinner party was to be given and the piece de resistance was to be fresh salmon, garnished with the luxury of out-of-season cucumber. Oh horror! The cucumber was found to have the teeth-marks of a child in the very middle of its smooth dark green skin. Who was guilty? The three of us were lined up and bullied to confess. No one did. My brother described the day as one of unutterable woe and doom, the very room seeming dark with the anger of the 'grown-ups'. At last, to his complete surprise, I confessed. 'I was utterly amazed', he said. 'I knew that I had imprinted those fatal teeth-marks! I could only conclude that as you were always the 'black sheep' by this time, in the confusion you thought that as usual you must have been the culprit. Or perhaps you were so fed up with the whole thing that you 'confessed' in order to get it all over at last. I let you take the blame, and to this day I feel guilty and that you are stronger than I.'

For punishment I was not allowed to go down to dessert, but was put to bed alone while the other two were dressed up and went down as usual. My brother did not eat his share of the spoils but brought them to me in bed. He did not tell me the reason for his generosity and I suppose I must have thought it was just his usual kindness and sympathy. However, I have no recollection of the event at all. His childish guilt had imprinted the incident on his mind. We laughed so much in recalling it, and other peccadilloes, that our children left the room in disgust, saying we were mad.

Thinking back to some of the games invented by us three children, I realise that, nonsensical as they were, they had a value to us beyond the superficial aspect of employing our imagination to amuse ourselves.

Perhaps the most obviously therapeutic of these was a game called 'Church'. I think my brother must have been about twelve and my sister and I nine and ten, when we played this game, and by that time we had certainly received a little religious instruction; in fact my brother had been confirmed, and it may have been his confirmation which started us off with the game. It was always played in the dining room, where we began by drawing the curtains and making it as dark as possible. The table was the altar, chairs were turned backwards, so that we knelt on the seat and rested our clasped hands and our foreheads on the back, making a sort of prie-dieu. I think my brother was usually the priest, though we girls were allowed an occasional turn. Standing on a stool, he addressed us in a strange mumbo-jumbo language, interspersed with a few real words, and these, though recognisable, were often mangled. The tone of voice was highly important, and was the most risible part of the game. The voice had to be what we termed 'parsonical', and a sort of chant was used, imitated I suppose from what we had heard in church. The other two children, as congregation, occasionally joined in with 'It is meet and right so to do' (also chanted) and 'Ah-ah-men'. The great difficulty was to suppress the gales of giggles that beset us. We thought it was excruciatingly funny and at the same time wickedly blasphemous. I think the sense of doing something naughty in the spookily darkened room was the charm of the game - while the giggling with which it invariably ended was most releasing. Somehow, when the curtains were drawn back and the room restored to normal, we felt that we had really been absolved.

Another game, played by my sister and me at an even earlier age, was the enactment of a tea party. There were two parts, which we took strictly in turn. First, one of us would be Lady Stiffigreyner, a stately and elegantly refined lady who had invited her uncouth nephew, Oswald, to take tea with her. Lady Stiffigreyner had the most meticulously, absurdly over-refined manners possible to invent (wherein lay the actor's artistry). She quirked her little finger when she held her tea cup, waved about a delicate handkerchief scented with lavender water, and was inclined to faint ('upon the sofa' as Jane Austen so delightfully puts it) when shocked. Oswald was a crude, ill-mannered child, prone to spill and break, and to our unutterable and slightly guilty delight, he used 'rude' words, belched unrestrainedly and had a rumbling stomach, causing his aunt to lie back, half fainting, flapping her handkerchief and exclaiming 'Oh, Oswald, Oswald!'. Of course we both preferred being Oswald, but turns were taken strictly and there were interesting possibilities to be got from the part of his aunt too! This rude game also resulted in shrieks of uncontrollable laughter and I suppose compensated in some way for the strict regime of 'table manners' to which we were subjected.

A third game, or perhaps it should be called a ritual rather than a game, which I remember vividly, continued well into late adolescence. It was performed when we felt listless, depressed or actively unhappy. I can't remember when it started, but I think we must have been quite small. If we had been frightened by half-overhearing a quarrel amongst the grown-ups, had had a bad day at school, a disappointment, or for some reason felt sorry for ourselves, we resorted to a strange, thumping, heavy-footed dance. The steps were carefully worked out and practised, and were performed to the tune of Grieg's 'Hall of the Mountain King', which we hummed tunelessly, when breath allowed, or we sometimes intoned part of the Witches' speeches from Macbeth, making the words fit in with the music. In fact I think we were supposed to be witches. We each held a dustbin lid raised on high, which we clashed together at appropriate moments. The dance went on till we collapsed, perspiring and exhausted. We called this ritual 'sweating the comedy out of our veins' and it interests me now that we used the word 'comedy'. Somehow, at some level, we must have realised from an early age that comedy and tragedy are very near and that our adolescent moods of depression were more than a little ridiculous. At any rate this absurd performance was most effective in banishing 'the blues'.

Sept. 1978

Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Co. had a bad influence on me in my schooldays. My sister and I, with a third close friend, modelled ourselves on Stalky, McTurk and Beetle, for whom we had a great admiration and whose exploits we strove to emulate. I still have a battered red leather copy of the book with its thin Indian paper underlined in pencil at the passages we thought most excruciatingly funny. All 'grown-ups' and particularly teachers were seen as our natural opponents and there was keen competition amongst us who could devise the most absurd and satiric trick to play upon them. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately for us) many of these ridiculous pranks misfired and we duly received the appropriate punishment. Rules were broken solely for the excitement of feeling ourselves to be heroes of rebellion, or alternatively proud martyrs, should we be discovered or outwitted and punished. One very appropriate punishment was meted out to us when we had disobediently failed to appear for a practice singing of the school song before a gym display. We were ordered to mount the rostrum in the big hall after morning prayer the next day and to sing the Harrow School Song to the assembled school. Not one of us three could sing a note in tune and we were very conscious of our ridiculously feeble voices. When questioned why we had not appeared at the practice, we had replied, truthfully if somewhat impertinently, that we couldn't, and wouldn't sing anyway, so that the practice was a sheer waste of time for us.

However we couldn't but admire the punishment devised for us, though we dreaded making such fools of ourselves. We set ourselves the task of circumventing authority in true 'Stalky' style. One of us came up with the brilliant idea of gaining the help of two large fat sisters of our acquaintance, both of whom had powerful soprano voices, quite capable of dealing with the evermounting high notes of "Follow up, follow up, follow up, till the field rings again and again with the tramp of the twenty two men." Joan and Joyce agreed to pretend that they too had sinned, and joined us on the platform loudly and joyously to sing, while we three culprits silently mouthed the words.

It was particularly noble of Joan and Joyce, as in the past they had been victims of one of our most successful games. This was called 'Local Colour' and the idea was to invent the most unlikely lie one could think of and to adorn 'a bald and unconvincing narrative' with as much verisimilitude as we could invent. One scored points for the number of people convinced, with bonus marks for members of staff or prefects. When Joan and Joyce were new girls, we, as another pair of near-age sisters, were asked to help them to settle down by initiating them into school ways. Poor girls, we told them that they were expected to eat the fruit from a large bowl in the headmistress's sitting room - we caused them to strip naked for an imaginary 'physical' with the gym mistress, and inflicted many other indignities on them. However, they bore no malice and it was not long before we were friends and they were playing 'Local Colour' with us. I think our greatest triumph (which also led to our downfall) was to spread the news that our elderly spinster headmistress (known as Poll) was secretly engaged to be married to our even more elderly gardener, the only man on the premises. We even inaugurated a collection for a wedding present, but the question of what to do about the money became a real worry and finally led to utter rout. A letter was written to our parents accusing us of being arrant liars and 'a bad influence'. We hotly defended ourselves and accused the Powers-that-Be of lack of humour, but punished we were - deprived of pocket money, sent to bed with the 'babies' and, worst of all, not allowed to go to the swimming baths for a whole term. It was known that swimming was the only sport at which we excelled or which we enjoyed, and it was indeed a punishment. For other crimes in the past we had been forbidden hockey or netball, or not allowed to watch matches, but it had become known (we saw to it) that this was a relief rather than a punishment for us. We were habitually disgracefully sneering and scornful about competitive games or school 'patriotism'. Our riposte to the accusation of lying was to tell the truth baldly and at the most tactless possible times. But alas, this too resulted in punishment. One prank I remember did not end in punishment, although, unknown to us, it must have caused some amusement at our expense amongst the staff. A nice young English teacher had suggested we should try our hands at writing a bit of blank verse. We had been studying an Elizabethan drama - all murder, blood and death, and this inspired us to present as a perfectly serious piece of work a long parody or skit, full of 'purple' rubbish. Everyone fell dead in the end, 'weltering in purple gore', and I can remember one or two meaningless lines which we thought masterly, such as 'And scrabbling up, plunged down the arabesques ... '. The whole thing was presented to Miss Knott as a serious effort. She must have had a good laugh, but she treated it with the utmost seriousness and even invited us to tea in her room, providing what we called 'sloshy' cakes. After tea she got us to read passages out loud. How she kept her face straight for so long I don't know, but we all ended up giggling helplessly and she certainly had no further trouble from us in her classes. The school had a hard job turning us into 'ladies', or rather 'gentlewomen', for the word 'lady' was said to be 'common'. However, I suppose there must have been some degree of success as I ended up becoming the headprefect a few years later, and, my goodness, wasn't I strict with little horrors such as I had been myself!

Nicholas Z was a pale, thin child when I first met him as a contemporary of my son at his Prep school. He was a sickly little thing with huge glasses and arms and legs like strings of cooked macaroni. He could throw a violent attack of asthma at the drop of a hat and was frequently said to be at death's door. His sad little face was often to be seen peeping from an upper window when the other boys were taken out by their parents. His intellectual family sent him the New Statesman and the Times Literary Supplement in lieu of sweets, fruit or comics when he was ill, but in spite of this, or because of it, he came top in all his exams, wrote poetry and from behind his spectacles his eyes had the wild, mad gleam of a precocious child from one of Saki's stories. Already he was adept at making scenes and manipulating others. Dreadful child though he was, I couldn't help liking him, for his tongue, though often bitingly sarcastic, could be brilliantly witty, and he had a magnificent zest for life.

My son ruled over an imaginary Universe when he was about twelve, and he spent hours devising languages (complete with syntax), histories of other planets subordinate to himself and ruled over by a series of imaginative friends who reported to him. Needless to say the ubiquitous Nicholas played an important role in this fantastic game.

During one summer holiday I received a telegram which puzzled me exceedingly. It stated that 'The Lord of Nihilum' would be arriving at five o'clock the next afternoon. Puzzled, I consulted my son - who enlightened me. The telegram was from Nicholas and it was followed the next morning by a letter inviting himself to stay, ostensibly to escape from his father, after whose name he put the word 'TERROR', in brackets and capital letters, every time it occurred. The whole letter was a magnificent jeu d'esprit and extraordinarily precocious. He addressed me as 'Dear Mother Figurine'.

Although he was a most trying guest, nevertheless I enjoyed his visit, and so did my two sons. The dash and courage of this puny, sick child was amazing, and there was never a dull moment. At times I could cheerfully have murdered him and I often went to bed at night swearing I would kick him down the stairs the next morning if I didn't actually kill him. He was infuriatingly faddy about food and had no hesitation in criticising what was put before him. One morning I was standing over the stove in the kitchen, angrily stirring something and muttering to myself about what I would like to do to him, when he appeared, wreathed in smiles, bearing a decanter from the dining room. 'Do let me pour you a glass of your own delicious sherry', he cooed,'they say it sweetens the temper.'

When I went to bed at night I would often find the brat sitting at my dressing table and he would then engage me in philosophical discussions, in the hope, I am sure, of forcing me to reveal my ignorance on some esoteric subject. I received not only a splendid bread-and-butter letter from him, but thereafter he frequently wrote to me from school and, if he was not ill, I took him out with us when I visited my own two sons. He won a scholarship to Winchester, so the boys were together again, and on one occasion my elder son was invited to his home for a visit. Mrs Z was known to us as the Duchess as she had an enormous fur coat and a very large and stately appearance. She occupied her spare time in coaching Greek and Latin for University entrance, and her husband, a dynamic little man of Russian origin, did something equally intellectual - I forget what now. As for Nicholas's eldest brother Serge, though also a clever child, he had been brought to the verge of a nervous breakdown by the shaming antics of his sibling. However, my son enjoyed his visit and said of the Duchess that 'it was a splendid sight to see her, her ample form swathed in a large apron, flourishing a frying pan and quoting Greek and Latin tags'.

The boys met less frequently when they left school. Nicholas won an open scholarship to Magdalen, Oxford, after carrying off almost every prize at school and editing 'The Wykehamist'. He continued to write to me from time to time but I did not see him for many years, until one day a few years ago he appeared unannounced, armed with flowers and a bottle of wine. I recognized him at once, though by now he was in his mid-thirties, six feet tall, with long frizzy hair tied back with a bootlace, and an American accent. He enfolded me in a large embrace and within ten minutes we were both crying with laughter as I reminded of some of the worst horrors he had inflicted on me. He could hardly believe some of the antics I recounted, which he swore covered him with shame, though he was laughing delightedly. His eyes still have that wild, zestful gleam behind the glasses, and his friendship has been one of the most amusing and rewarding of my life.